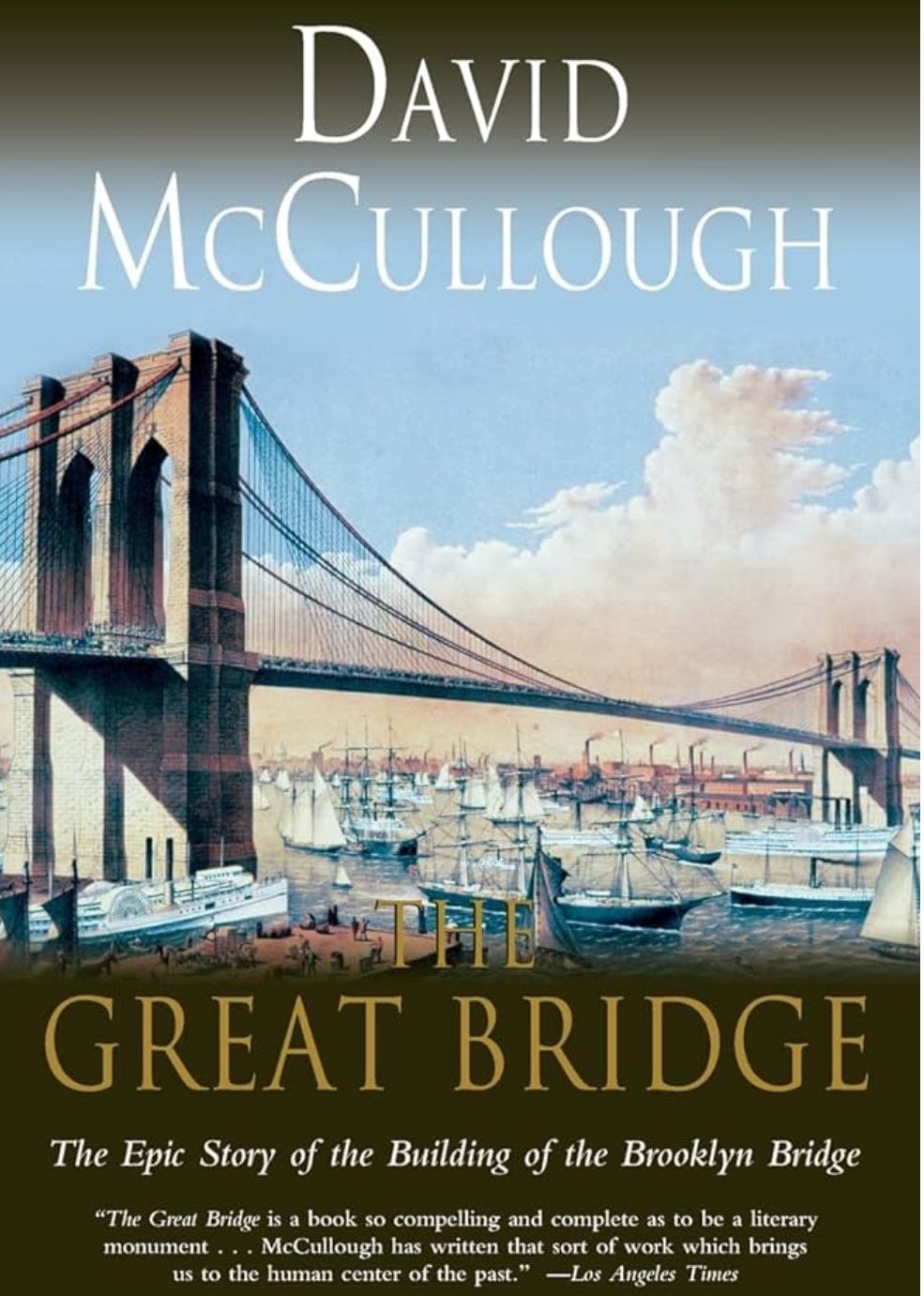

Since its inception, New York has always been building, building, building. We walk around construction sites, peer at them through wooden slats, and naturally being New Yorkers, we complain about them. But the Brooklyn Bridge built in the late 19th century remains high on the list of the most cherished.

In his 1972 book “The Great Bridge,” David McCullough goes into detail—often bordering on minutiae—about the building of the BB, which began in 1869 and lasted 14 years. Chief Engineer John A. Roebling, a German-born engineer by trade, emigrated to America in 1832 as he saw the New World as a land where “a man was free to make the most of his abilities if he had personal energy and power of wills.”

After a brief, unsuccessful attempt at farming in Pennsylvania, JAR pivoted and proceeded to design and build bridges in Cincinnati, Pittsburgh and Niagara Falls. In the meantime, he also came up with the idea of using iron rope instead of hemp in suspension bridges. By the 1850s, he set his sights on something that had long been a dream of many New Yorkers: a bridge that would link Manhattan and Brooklyn—two separate cities back in the day.

Once a bill was passed by New York State and both private and public funds became available, JAR and his team set diligently to work. Unfortunately just as the task was getting underway, he suffered a freak accident, contracted tetanus then lockjaw, and died a year into the project.

Fortunately his first-born son Washington Roebling had been well schooled by his father and it was he who saw the vision of JAR realized. (This confusion about which Roebling deserved the credit followed WE to the ends of his days, and continues even today.)

McCullough provides detail upon detail — too many frankly—about every aspect of this New York landmark, starting with the construction of the caissons that would help secure the bridge tower foundations. A caisson was a football-stadium-sized wooden structure shaped like a gigantic box, with a heavy roof, strong sides, and no bottom.

Filled with compressed air, each caisson would be sent to the bottom of the river by building up layers of stone on its roof. The air would keep the river out, help support the box against the pressure of water and mud, and make it possible for men to go down inside to dig out the riverbed. As they progressed and as more stone was added, the box would sink slowly, steadily, deeper and deeper, until it hit a firm footing.

A caisson would accommodate 132 workers at one time, almost all of whom eventually suffered the ill effects of being submerged for hours at a time—and who needed hours more to recover once they reemerged. One of these victims was WR himself, who contracted a case of the bends and suffered from its aftereffects for the rest of his life.

As with everything in New York, politics entered into the Brooklyn Bridge fray, as Boss William Tweed and his “Ring” muscled their way in—illegally of course—and were rumored to have stolen $200 million during the construction period. Tweed was eventually convicted and sent to jail where he died ignominiously in 1878.

Public enthusiasm about the BB however never subsided as hundreds of New Yorkers gathered daily to watch every stage of the construction—including the the building of the majestic towers on both sides of the river (the highest buildings in NY at the time).

Finally, after 14 years of equal parts opposition and support. the bridge opened to great fanfare on May 24, 1883. Due to illness, WR watched from his window but his wife Emily was on the bridge during the festivities, along with the mayors of New York and Brooklyn as well as US president Chester Arthur. Emily was rumored to be the brains behind the bridge (“Gilded Age” fans, take note) and as WR could not speak for very long, she basically was.

The BB became so popular that a week after it opened, a stampede of visitors led to the death of 12 people.

WR himself outlasted all the contoversy. He outlived all 3 of his brothers and lived to the age of 89. The rest is history as the BB went on to become the subject of songs, posters, movies, even jokes—“all this trouble,” comics would often kvetch. “And just to get to Brooklyn.”

It was billed as the Eighth Wonder of the World and still draws visitors from every corner of it. And what Brooklyn mayor Seth Low said about the bridge 150 years ago holds true today.

“The beautiful and stately structure fulfills the fondest hope," he said at the time. “The impression upon the visitor is one of astonishment that grows with every visit. No one who has been upon it can ever forget it. Not one shall see it and not feel prouder to be a man." What a bridge. What an accomplishment. What a book.

It never ceases to astonish me.

Thank you, thank you, thank you! I've been desperate for a good/great book to read and I just downloaded the ebook!