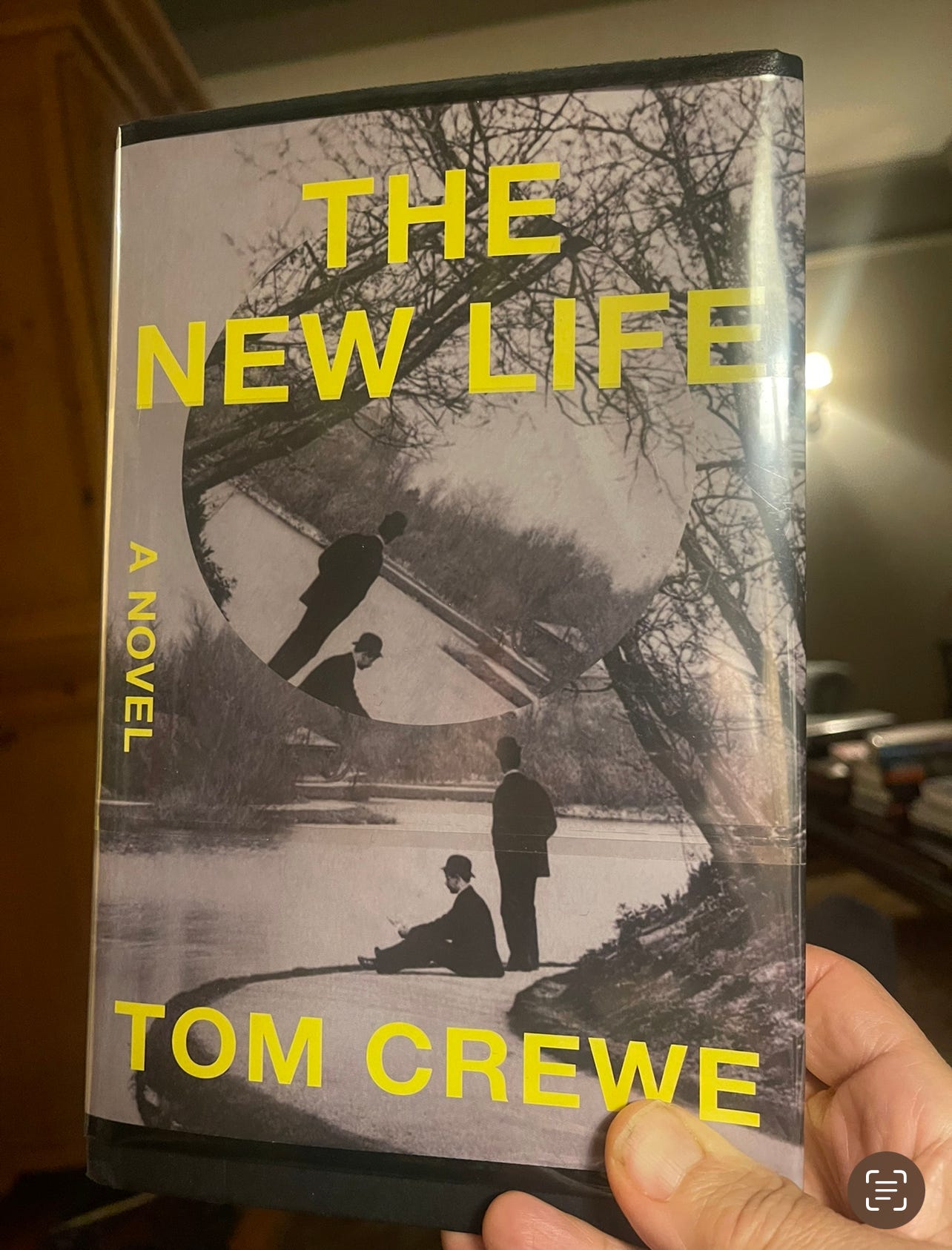

Books: “The New Life” by Tom Crewe

The 19th century was a big time for revolutions. The Industrial Revolution, which began at the turn of the century, reached its apogee in 1840. Eight years later, there were republican revolts against monarchies across Europe—which drove many disillusioned citizens to the Americas.

But the seeds of a lesser known revolution—a sexual one—were also planted in the 19th century. That’s the subject of “The New Life” Tom Crewe’s bold and eloquently written new novel.

TNL is a novelization of the real-life working partnership between John Addington Shipley and Henry Havelock Ellis, two British intellectuals who might be considered the Masters and Johnson of their time. But they went a little further than M & J ever did.

John and Henry envisioned a “New Life,” where men and women were free to love others of the same sex. Unfortunately, this flew in the face of reality and the law: homosexuality in England was still considered a criminal misdemeanor in the 19th century, punishable by two years in prison. (Side note: this would last until 1967).

The narrative alternates between John’s POV and Henry’s. John, a firebrand by temperament, is a married man of means who nevertheless cruises London’s parks and dark alleys for anonymous sex. Henry who is straight is married—but his wife is attracted to other women. Through mutual acquaintances, John and Henry are introduced, begin corresponding, and agree to write a book about “sexual inversion,” which is what LGBT relations were termed in the late 19th century.

After a number of anonymous interviews with promiscuous gay men, Henry and John’s book is finished and ready for publication—as a purely “scientific” tome—until the Oscar Wilde trial erupts in 1895. Respectable publishers drop it like a hot potato. John, ever the idealist, wants to proceed with publication anyway. Henry doesn’t.

Who is right here? John, who wants the “love that dare not speak its name” to come out of the closet and start talking? Or Henry, who fears imprisonment and permanent disgrace—both for himself and his family—should the book see the light of day.

Crewe, a Cambridge man and an editor at the London Review of Book, writes prose that puts one in mind of E.M. Forster. Forster would face a similar conflict of should I/shouldn’t I publish with “Maurice,” his gay novel which was finally published, albeit posthumously, in 1971.

Since the mid 19th century, society has evolved. Same-sex relations are now accepted in most developed countries. This novel is a much needed reminder of where we were—and how far indeed we have come.