In 1964, the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan show and proceeded to change musical and social history. The Civil Rights Act was moving through Congress and was beginning to look like something real.

And in a crowded stuffy courtroom in Dallas, packed with spectators and reporters from all over the world, the trial of a man who changed history in his own way was getting underway. The man was Jack Ruby.

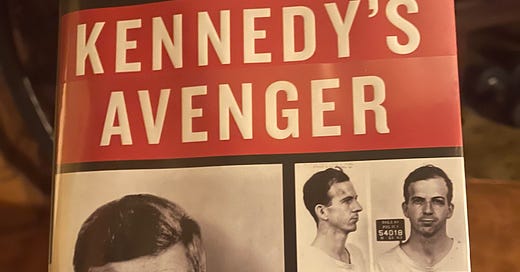

A sleazy mobster-type, and an owner of strip clubs (as well as dogs he referred to as his “children”), Ruby became famous, and infamous, for shooting Lee Harvey Oswald a day after Oswald shot Kennedy. Nobody who was alive during those awful days in November (I was nine) can forget the television image of the white-suited, strapping dude wearing a white cowboy hat plowing a gun into Oswald and Oswald grimacing.

In “Kennedy’s Avenger,” Dan Abrams and David Fisher recount in fascinating detail the difficulty of not only selecting an impartial jury for Ruby’s trial, but also for prosecuting a man in a city that was itself on trial. Because of the Kennedy assassination, Dallas had become known as the “city of hate.”

Ruby’s defense team was led by Melvin Belli, a volatile, flamboyant lawyer (in the mold of F. Lee Bailey and Johnny Cochrane). His task was to convince the jury that Ruby was insane at the moment he shot Oswald and had suffered from mental illness for many years prior.

In the corner for the prosecution was Henry Wade (who later became the Wade in Roe v. Wade!) His aim, and that of his team, was to prove Ruby was of sound mind and that he did indeed deserve the death penalty.

Jack Ruby never took the stand, but dozens of expert witnesses on both sides did, sometimes fascinating the jury but often boring and confusing them. They were sequestered in the country courthouse for months. One juror actually fell asleep during Belli’s closing argument.

As a youngster with other things on his mind back then (Beatles albums and stamp collections), I didn’t pay much attention to the trial nor could I recall what the verdict was. The skillful, page-turning style of Abrams and Fisher had me guessing up to the last minute. Their discussion of the aftermath (which dragged on till 1966) was just as riveting.

This superb book’s exacting scholarship touches on a topic that still resonates with many of us—the murder of a popular young president. People

will be discussing conspiracy theories about JFK’s death for years. This is a switch—a focus on the man who killed a killer.