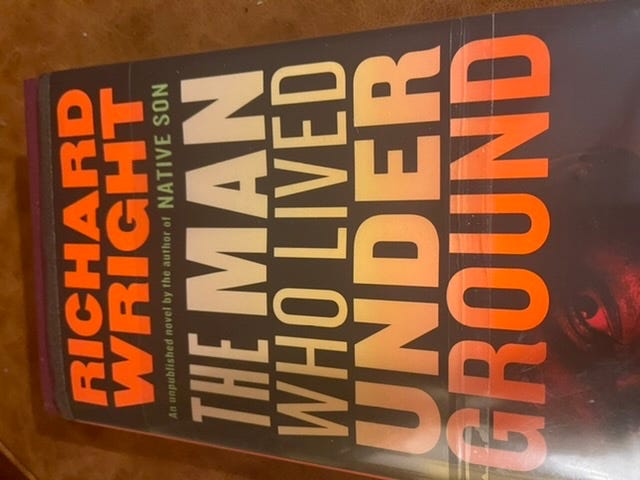

The Man Who Lived Underground

By Richard Wright

In 1941, fresh off the success of his novel “Native Son,” Richard Wright began work on a short story called “The Man Who Lived Underground.” He got the idea from a newspaper story he read about a man who one day decided to disappear into the sewers of Los Angeles.

Besides the short story which was anthologized some years later, Wright also wrote a novel-length version of the story, which was inexplicably rejected by a major publishing house. Only recently, through the grace of RW’s estate (and his grandson Malcolm) can we see the whole story the world missed out on.

And man, what a story.

Fred Daniels, a young black man, is walking down the street one night when he is suddenly accosted by three white detectives. They drag him into a cop car, and take him down to the station where he is accused of murdering and robbing a white couple, who lived next door to the home where he had been working as a day laborer.

Confused and horrified (this is the 1940’s, before people had lawyers and you were read your Miranda rights) he protests his innocence only to continue to be accused anyway—as well as slapped, punched and pistol-

whipped. By the grace of God—or sheer luck—he sneaks out of the station when the detectives’ backs are turned, runs into the street and in a moment of panic, lifts up a manhole cover, and disappears into the sewer.

There, he begins an underground journey through the sewers and basements of this unknown city (although I believe it is somewhere in Westchester County, New York), crawling under, among other things, a church, a funeral home, and a jewelry store. He makes his way through the tunnels with the use of tools he finds in one of the basements, digging and scraping through brick and mud, often narrowly missing a fall into the filthy sewer water. It is a journey right out of Greek mythology—something that’s worlds away from even the scariest shows running on Netflix these days.

Not planning to give away the ending (hint: it’s a doozie.) But in “Memories of my grandmother,” his companion essay to the novel, he explains that the feeing of being on the outside looking in is key to understanding the novel.

But let’s not mince words here, people. This is about man’s indignity to man, and when that man is Black and automatically assumed to be the killer because he’s Black, that indignity is called racism.

A terrifying read. But absolutely terrific.

There is a big claustrophobic world of subterranean stories by African American writers. Ralph Ellison’s titular Invisible Man creates a sub-basement retreat for himself, complete with light & power. In nonfiction, Grand Central Winter by Lee Stringer details a stretch of his city years spent precariously sleeping and storing his few possessions in a sort of shallow rafter at the top of a subway tunnel - I no longer own the book, so can’t offer more specifics, but Stringer goes into mesmerizing detail on how he managed to do this. I’m certain a curious reader will find more examples.

Disappearing when we want to and reappearing when we’re ready is another privilege people who aren’t poor or despised (or both) take for granted.

Richard Wright is the reason I became a writer AND have had a life long interest in racial issues. “Black Boy” devastated me as a 12 year old growing up in 1970s New Jersey.